The magic

in the detail

We go behind the scenes at

the Natural History Museum to

explore the curious collections and

overlooked treasures beyond Hintze Hall

All images by Jonathan Gregson

It’s 8am and all is quiet in the museum. Hope the blue whale soars through Hintze Hall, her colossal skull tilted towards the entrance doors as if she might glide out into the street at any moment. Her only audience at this hour are the troop of stone monkeys that peer around columns at the hall’s edge, and the various fossilised beasts that stand in its shadows.

The entrance to the Natural History Museum inspires reverence no matter how busy it gets, but standing in the ‘cathedral of nature’ when it’s empty is positively a religious experience. I half expect the stone statue of Charles Darwin to rise from his chair on the main staircase and give a sermon.

As the clock ticks towards opening hour, the museum slowly awakens. The animatronic T. Rex in the dinosaur gallery, its head still bowed as if in slumber, begins to roar. Crickets chirp. Globes spin. Audio commentaries start up. There’s a gentle swish and slap as cleaners work their way across the mosaic floor with wet mops. The patinated railings leading up to the first floor are polished to a gleam, and a faint smell of Brasso lingers in the nostrils.

I’m here to meet Miranda Lowe, principal curator of crustacea and an expert on one of the more curious treasures on display in the museum. To find her, I head away from the hall, slipping through a discreet doorway marked ‘staff only’ and into the bowels of the Gothic building. Here, dim corridors lead off dim corridors, their walls pasted with HR notices and befuddling maps. I peer into side rooms, catching brief glimpses of offices piled high with boxes, folders and plastic crates; staff tapping away at computers; workshops full of tools; a taxidermised crocodile and a large fish mounted on a spike. Everywhere there are cabinets – metal ones, wooden ones, glass ones. They contain records of some of the museum’s 80 million specimens, and are soon to be replaced in a mammoth project to digitise each and every one.

Passing through an office stacked with jumbled trays of shells, I enter another office, this one containing empty jars, microscopes and shelves holding books on subjects such as earthworm ecology and the freshwater leeches of the British Isles. Beyond this is another office, and here is Miranda.

She pulls on a pair of surgical gloves, opens a grey metal cabinet and takes out several grey boxes and clear plastic tubs. She carefully unties the thick cord holding one box together, and its sides fall open to reveal the most impossibly delicate object I’ve ever seen: a glass model of a tiny marine invertebrate called a Raphidiophrys. Glass spines as ethereal as the threads of a spider’s web radiate out from a central globe. I’m nervous to breathe in case they snap. As Miranda opens more boxes containing more impossibly delicate objects, I ask if any have broken. “All I can say is that none have ever broken with me!” says Miranda with a laugh. “But they're extremely fragile.”

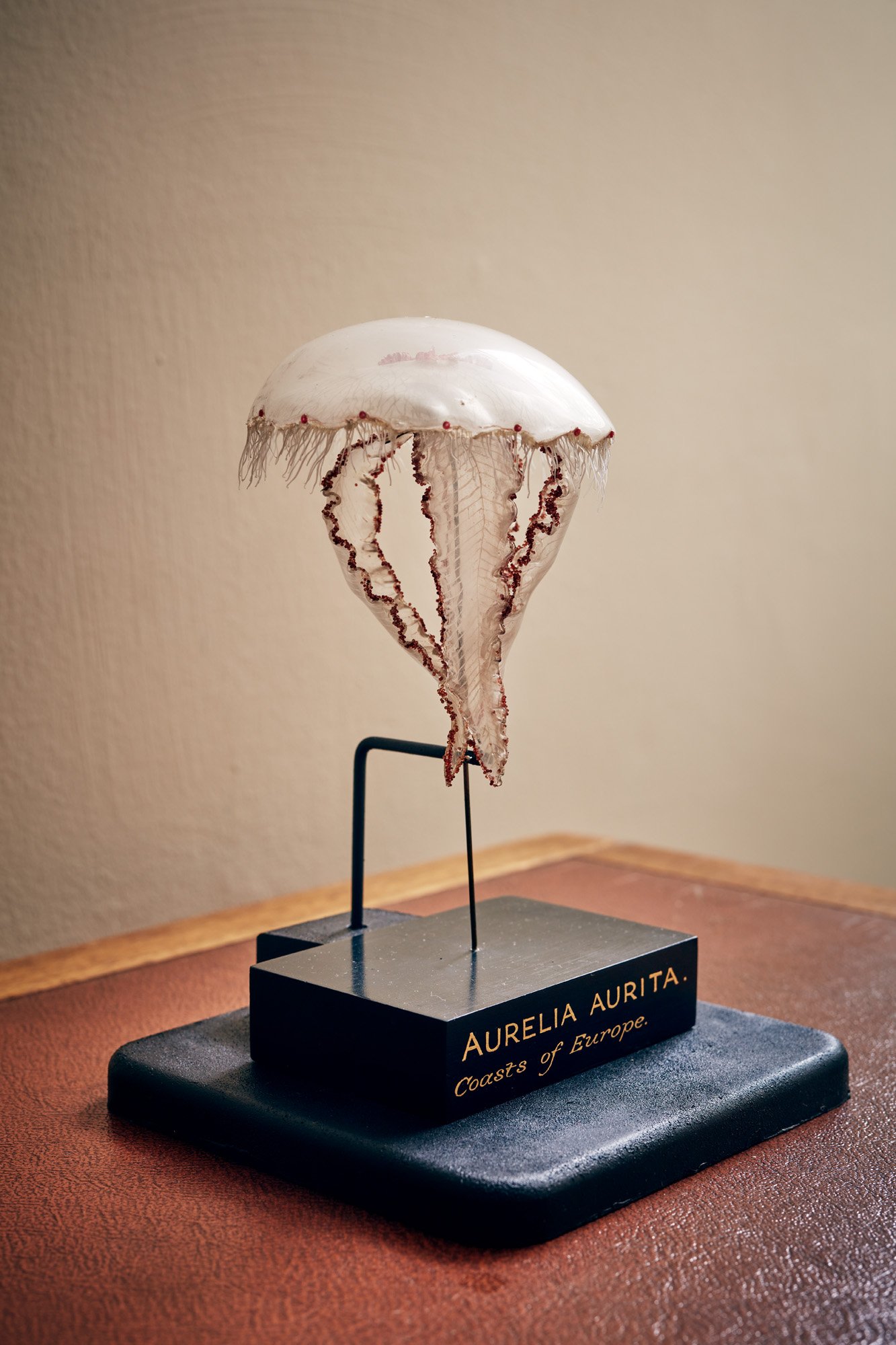

The Raphidiophrys is the culmination of a lifetime of work by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. The father and son started their careers in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) making glass eyes and glass flowers. On a sea voyage to the States in 1853, Leopold became fascinated by the jellyfish he saw floating near the surface, and was inspired to turn his (non-glass) eye to creating marine animals. “They started with sea anemones and then moved on to more complex organisms,” says Miranda. “The Raphidiophrys was made around 1889, when their work had progressed.”

The Blaschkas’ sea anemones are no less impressive for their naivety. Miranda shows me a couple of examples that are convincing enough that you might mistake them for the real thing if you placed them in a rock pool. And that’s precisely the point. Take a marine invertebrate out of the sea, and it instantly loses its form. Preserve it in formaldehyde, and it loses its colour. “The Blaschkas were displayed alongside real specimens in museums so people could getinsight into the colour and shape of the creature,” explains Miranda. “For those who couldn’t afford to do that Victorian thing of going to the seaside and taking the waters, this was the only way people could know what they looked like.” Word soon spread of the skill of father and son, and models were commissioned for display in natural-history museums across the world.

Miranda’s own interest in marine life started at the bottom of rock pools on family holidays to the Isle of Wight. Her interest in Blaschkas came much later, and she discovered the museum’s collection by chance in the 1990s. “I was relatively new here and was tasked with measuring and cataloguing glass jars,” she explains, locking the models back into their cabinet. “I found these glass sea anemones just lying on a shelf along with all of these other things pickled in jars.” At a science conference in Newcastle, she was drawn to a model of Noah’s ark in a glass case: “at the bottom were these sea anemones just like the ones I’d seen. The label said they were made by a father and son team: Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka.”

The discovery sparked a lifelong passion that has seen her travel all over the world on the hunt for models. The Blaschkas made over 10,000, and the museum’s own collection numbers 185. Despite all her research, an enduring mystery is how the Blaschkas were able to create such intricate works. No-one has since been able to replicate them. “I've shown them to a number of modern glass artists and they’re amazed at how they made them,” says Miranda. “I've picked up how they did certain things, working with lacquer and wire and enamel, but not all.”

These days, Blaschkas are hotly sought after by art collectors; models that were once sold as teaching aids for two Deutschmarks now reach £25k at auction. To appreciate their original purpose, we ascend to the tank room. It’s like some mad scientist’s laboratory. A glass tank, some nine metres long, sits in the centre, surrounded by low steel cabinets. This is home to Archie, a rare example of a nearly complete giant squid shipped over from the Falklands. “She came in frozen,” says Miranda. “There were 10 of us bringing her in, carrying her across the car park.”

On the shelves surrounding Archie are every shape and size of jar, containing every shape and size of sea creature. Doleful eyes peer out through the glass, bodies slumped at the bottom of jars filled with pickling alcohol. All the colour has washed out of them. If you’d never seen an octopus, you’d have a tough time imagining what one looked like from the gelatinous white blobs presented here. “You can see now how important the Blaschkas were,” says Miranda. “They brought all these creatures to life.”

Miranda’s professional life revolves a great deal around things in jars. She’s responsible for her own enormous archive, and she shows me some of the specimens of crustacea kept in row after row of cabinets near her laboratory. She opens one tall jar to tweezer out a pair of lobsters, explaining how tiny differences in anatomy help identify their species. The instant hit of formaldehyde takes me straight back to GCSE biology, and the imminent prospect of mouse dissection. Miranda laughs. “You get used to the smell. I don’t really notice it any more.”

Like the Blaschkas, a lot of Miranda’s work deals with creatures too tiny to view with the naked eye. High-precision microscopes bring these to life these days, rather than delicate glass models. “So many of the things I look at are microscopic but they’re crucial to sustaining life and the natural world,” says Miranda. “My little critters are going to get eaten but they sustain the life above. The krill and the arthropods are just as important as the blue whale.”

On the face of it, the two worlds Miranda inhabits, of science and art, laboratory and cathedral, make strange neighbours. But, as the Blaschkas showed, if you can find new ways to present natural history, you make a whole lot more people invested in it. “When you work with artists,” Miranda explains, “that’s how people can get a view of why we should care about nature, and how valuable it is to us.”

Miranda’s professional life revolves a great deal around things in jars. She’s responsible for her own enormous archive, and she shows me some of the specimens of crustacea kept in row after row of cabinets near her laboratory. She opens one tall jar to tweezer out a pair of lobsters, explaining how tiny differences in anatomy help identify their species. The instant hit of formaldehyde takes me straight back to GCSE biology, and the imminent prospect of mouse dissection. Miranda laughs. “You get used to the smell. I don’t really notice it any more.”

Like the Blaschkas, a lot of Miranda’s work deals with creatures too tiny to view with the naked eye. High-precision microscopes bring these to life these days, rather than delicate glass models. “So many of the things I look at are microscopic but they’re crucial to sustaining life and the natural world,” says Miranda. “My little critters are going to get eaten but they sustain the life above. The krill and the arthropods are just as important as the blue whale.”

On the face of it, the two worlds Miranda inhabits, of science and art, laboratory and cathedral, make strange neighbours. But, as the Blaschkas showed, if you can find new ways to present natural history, you make a whole lot more people invested in it. “When you work with artists,” Miranda explains, “that’s how people can get a view of why we should care about nature, and how valuable it is to us.”

I leave Miranda to her glass jars. Before I exit the museum, though, I have one last visit to make. I make my way back through Hintze Hall, up the staircase past Charles Darwin and into the Cadogan gallery. It’s a dark, narrow place, with stained-glass windows on either side. It’s here, in a room that looks like a chapel, that the museum displays specimens of particular significance: a skeleton of a dodo; the world’s oldest bird fossil; a first edition of On the Origin of Species.

Among the exhibits are three glass models: an octopus with one yellow eye staring up at the ceiling; a squid coloured red, turquoise and yellow; and a tiny marine organism called a radiolarian, with spindles thin as hair radiating out from two orbs, one inside the other. I’m not sure which is more unlikely: that such a creature exists in nature or that it was once re-created in glass. It’s hard to fathom, too, that objects of such rare beauty lay forgotten in museum storage for so many decades. It’s thanks to Miranda that the Blaschkas now claim their rightful place – in a gallery of treasures, where they sparkle in the dark.

This feature first appeared in the first issue of Good Place magazine.